(This article was originally published in "Games

International", issue #2 and is reproduced here with the permission of Brian Walker,

the former GI editor)

KREMLIN

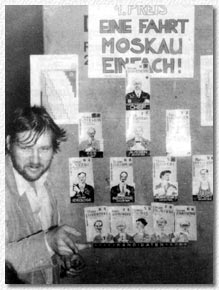

The object of Kremlin (reviewed last issue), is to

manipulate mythical politicians in the Soviet Politburo with the aim of becoming Party

Chief and waving at the October Parade in Red Square. In its first life Kremlin was

designed by Urs Hostettler (pictured above) and published by his company Fata

Morgana, in Berne, Switzerland. In this short feature, Urs describes how he got the idea

for the game, and his opinion of the newly released Avalon Hill version.

The object of Kremlin (reviewed last issue), is to

manipulate mythical politicians in the Soviet Politburo with the aim of becoming Party

Chief and waving at the October Parade in Red Square. In its first life Kremlin was

designed by Urs Hostettler (pictured above) and published by his company Fata

Morgana, in Berne, Switzerland. In this short feature, Urs describes how he got the idea

for the game, and his opinion of the newly released Avalon Hill version.

How does one go about designing a game like Kremlin? It's a question I've been

asked on more then one occasion.

Well, it all started one night in March 1985, as I was watching TV at home in Berne.

Tschernenko had just waved the long goodbye a few days earlier, and already the silver

screen was awash with speculating specialists attempting to predict his successor.

Old man Gromyko was Foreign Minister at the time, and as such, was able to nominate

the new Party Chief. The hot money was on Marshal Ustinov who was just approaching the

peak of his career at 80. In the background were two young turks, Gorbachev from Moscow,

and Romanov from Leningrad. Both were in their late fifties and thus had a lot to lose

should their bid for power fail (you don't get a second chance).

As I was listening I played around with some cards and decided to create my own

Politburo, and work out a mechanism that would respect the principles of gerontocracy

(the rule of the old), but allow a hidden strategy whereby younger members also stood a

chance of gaining power.

I worked on the game system for Kremlin for about one year. Both Sigma

File (Gibson's), and Down With the King (Avalon Hill) were strong

influences in terms of game mechanics. At one point we thought of changing the setting to

the Vatican, with the Pope taking the place of Party Chief, and visiting foreign

countries instead of waving. But then the situation in Moscow changed so dramatically

that we wondered if some evil Russian game developer had stolen our ideas; Ustinov died,

Romanov was demoted to candidate status, and Gromyko got the heave from the foreign

ministry. Thus, Kremlin was born.

One of our objectives when designing Kremlin was to produce a simulation of

Soviet political culture, which is why we place so much emphasis on controlling

characters in secret. Thus a player who has been playing very aggressively and dominating

the game, can find himself rudely upstaged at the climax when he discovers that the

character he thought he was controlling and who has been waving like a Queen, was really

controlled by somebody else!

So in this sense it can be seen that our version is much more of a psychological game

than the Avalon Hill one; a player can win by simply doing nothing the entire game.

This is not a criticism of the AH version which I know went through a lot of rigorous

playtesting. My main qualms were about re-situating the game in the eighties. Originally

the game was set in the fifties - the grey era of Soviet politics. My intention was to

satirize this period. I don't really think many aspects of the game apply to what

Gorby is currently trying to achieve, though this is something of a political point and

does not affect play in any way.

As to the game itself, I am inclined to think that their version is more suitable for

the American market with its emphasis on action. It can be quite boring to sit around for

two hours doing nothing, except revealing victory at the conclusion. But being perverse

by nature, how I like to win this way!

But what of the American version? Better? Worse? or merely different? Our editor,

who was partially responsible for AH's decision to take the game, describes the

Kremlin campaign.

My brief from Avalon Hill was simply to write the character cards for their version.

However, their head of development Don Greenwood knew I'd played the game several

times in its original form, so sought my advice on some of his proposed rule changes.

When I read the first draft for these changes my heart sank. My American colleague Alan R

Moon had already seen the changes and had inevitably chimed in with his

two-penn'orth. Even so, I wasn't prepared for the changes that Don had wrought.

Rightly or wrongly, Avalon Hill had acquired a reputation for making games more complex,

merely for the sake of it. At first glance, Don's changes seemed to confirm this

view. How wrong can a comrade be? My initial reaction was along the lines of 'why

change a winning team?' After all, the game had sold very well in Europe, even with

minimal production standards and limited distribution. Some of the changes seemed petty,

like changing the 'Kremlin Wall' (under which Soviet heroes are buried) to the

'Graveyard'. To his credit Don later admitted that this was 'dumb' and

reinstated the unique Soviet structure.

Like many who had played the original game I was

disappointed to see Anatol Fuckoff and Andrei Pissin purged, but this was expected so no

resistance was offered. Don also asked me to come up with some alternative names for the

characters as it was felt that the Teutonic humour of the originals would be lost on the

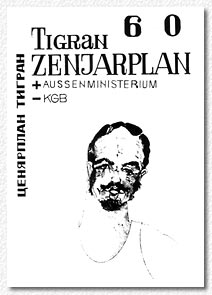

English speaking market. I demurred; apart from having a sentimental attachment to Tigran

Zenjarplan et al, I felt that they added atmosphere to what was already a

'foreign' game. Attempting to change the names into jokey English ones seemed

unnecessary, though I did agree to come up with two to replace Anatol and Andrei. As I

didn't hear from Don again on this point I assumed that the originals were to be

retained. It wasn't until I saw the finished product that I was aware the names had

been changed. My own afterthought contributions had missed the deadline anyway, but who

knows, perhaps Betty Boobsky might turn up in a future edition?

Like many who had played the original game I was

disappointed to see Anatol Fuckoff and Andrei Pissin purged, but this was expected so no

resistance was offered. Don also asked me to come up with some alternative names for the

characters as it was felt that the Teutonic humour of the originals would be lost on the

English speaking market. I demurred; apart from having a sentimental attachment to Tigran

Zenjarplan et al, I felt that they added atmosphere to what was already a

'foreign' game. Attempting to change the names into jokey English ones seemed

unnecessary, though I did agree to come up with two to replace Anatol and Andrei. As I

didn't hear from Don again on this point I assumed that the originals were to be

retained. It wasn't until I saw the finished product that I was aware the names had

been changed. My own afterthought contributions had missed the deadline anyway, but who

knows, perhaps Betty Boobsky might turn up in a future edition?

As to the rule changes, my main concern was the removing of the hidden influence

points and being able to win with three different wavers. I felt the effect of

this would be to produce a more muddled game, lacking the clarity and the psychological

elements of the original. The crux of the argument was that I felt Kremlin was

essentially a fun game, while Don seemed to be trying to turn it into an altogether more

strategic affair via increased rules.

Then there were the political problems inherent in re-situating the game in the

eighties and sticking Gorbachev on the cover. Urs and I were adamant that the game was

meant to reflect the Cold War period under Stalin, and was in no way representative of

Gorby and perestroika. Don countered this by stating that having a recognisable

and topical figure on the box would help increase the game's 'saleability':

an assertion with which I could never agree.

By now letters were flying backwards and forward across the Atlantic on a daily basis.

Superficially it was almost a Hollywood scenario; the creative artists seeing their

masterpiece disfigured by a monolithic corporation. But that's a rather pretentious

notion; in truth we both knew that Don was working very hard to produce the best possible

result for all parties.

Eventually though, our persistence paid off; Don agreed to reinstate the original

rules, albeit in a shaded area in the rulebook, a move that had the faint whiff of

tokenism, a feeling compounded by the somewhat less than complete rules in this section.

In addition there were also to be basic and advanced rulebooks which mollified us

somewhat. By this time though, my guns were firmly trained on the cover. I felt more

strongly about it than Urs, who was more philosophical, remarking that the 'Americans

probably understand then-market better than us'. Be that as it may, the Gorby cover

has now been ditched in favour of a colourful collection of Soviet iconography, making

the game appear less serious. Little wonder Don was to remark later: 'This was the

toughest game I've ever worked on'.

But to return to the original question; is Kremlin now a better game?

After all the static I gave Don he'll probably kill me when I say, yes, I believe it

is. In retrospect, I think I probably suffered a knee-jerk reaction to the changes per

se, rather than the effect of these changes, in my mistaken desire to retain the

'purity' of the original. Ugh! these words taste awful.

The Kremlin Reshuffle

Declared Influence

The main change from the original is the removal of secret influence; in the original

a player could win if he had as much or more undeclared influence points in the

Party Chief as the player controlling him openly. It is still possible to have the

best of both worlds here by adopting the rule that a player can still claim a wave for

his faction by declaring influence points equal to, or in excess of the player

controlling that politician, immediately prior to phase 8 (Waving at the October Parade).

Of course it is also possible to play the game as per the original rules, but bear in

mind that in this version declared influence points are not lost if the politician is

dispatched to Siberia, something the American rulebook fails to point out.

Three Time Wavers

The second major change is the ability to win if your faction has waved three

times, irrespective of who did the waving. In the original, the same politician

had to wave three times for victory to be claimed. The effect of this is to make the game

more fluid. In the Swiss version it became very difficult to become a three time waver,

especially in a five or six player game.

Siberia I Declare

Losing declared influence points on politicians dispatched to the icy wastes is, at

first glance, a fairly radical change. The effect of this should make players more

circumspect in their bidding. But in reality players become power crazed and go the whole

hog anyway, thus rendering this change rather less radical than it appears initially.

Tie Breaker

This has to be one of the best changes Don came up with. Ties are now broken by the

player with the third highest declared influence points on a particular politician,

rather than simply by the player who declared first, though this method is still used in

the event of ties unresolved by the first method.

The effect of this is to involve more players in decision making which is always a

good thing in any game, but especially this one.

The Options

Optional rule should there be no Party Chief at the end of phase 5 in year

eleven: Although this situation does not often occur it can be a problem when it

does, as it means that a player controlling the Foreign Minister decides who will win the

game by announcing the next Party Chief. Clearly not a satisfactory solution. To resolve

this, we suggest that the winner is the faction with the most recorded waves. In the

event of a tie then the player controlling the highest ranked politician wins the

game.

Jobs For The Boys

The plus and minus signs on the politician cards refer to their suitability for

certain offices. We seldom used this in the original but that was more due to the

fiddliness of constantly changing ages, but more relevantly it was so difficult to get

anyone to wave three times, let alone make sure that your men had the jobs. Now both

these factors have been eliminated this option seems a good one since it makes the

promotion phase considerably more strategic.

Adding Influencing Points

Should be considered mandatory rather than optional.

The Intrigue Cards

Difficult to decide about the usefulness of these. Certainly they add uncertainty and

make for a more fluctuating game, but rather at the expense of planning. The blackmail

cards are not my cup of vodka at all, though this is more to do with my distaste for

games where you have to strike bargains with players.

Historical Revolutionary Variant

This is the new expansion kit released by Avalon Hill featuring historical

politicians. So a big hello to Josef Stalin. The concept of having real politicians who

are replaced by mythical politicians when they die is indeed a wonderful one.

Unfortunately it simply doesn't work. The main problem is one of age. Uncle Joe

checks in at 44, so no matter how much purging he does you can be sure it will be a long

time before he checks out.

Likewise Leon Trotsky (45), and Nikita Krushchev (30). The suggestion I would make is

that you add 30 to the ages of the 'real' politicians.

Let's hope I don't end up eating these words as well.

The object of Kremlin (reviewed last issue), is to

manipulate mythical politicians in the Soviet Politburo with the aim of becoming Party

Chief and waving at the October Parade in Red Square. In its first life Kremlin was

designed by Urs Hostettler (pictured above) and published by his company Fata

Morgana, in Berne, Switzerland. In this short feature, Urs describes how he got the idea

for the game, and his opinion of the newly released Avalon Hill version.

The object of Kremlin (reviewed last issue), is to

manipulate mythical politicians in the Soviet Politburo with the aim of becoming Party

Chief and waving at the October Parade in Red Square. In its first life Kremlin was

designed by Urs Hostettler (pictured above) and published by his company Fata

Morgana, in Berne, Switzerland. In this short feature, Urs describes how he got the idea

for the game, and his opinion of the newly released Avalon Hill version. Like many who had played the original game I was

disappointed to see Anatol Fuckoff and Andrei Pissin purged, but this was expected so no

resistance was offered. Don also asked me to come up with some alternative names for the

characters as it was felt that the Teutonic humour of the originals would be lost on the

English speaking market. I demurred; apart from having a sentimental attachment to Tigran

Zenjarplan et al, I felt that they added atmosphere to what was already a

'foreign' game. Attempting to change the names into jokey English ones seemed

unnecessary, though I did agree to come up with two to replace Anatol and Andrei. As I

didn't hear from Don again on this point I assumed that the originals were to be

retained. It wasn't until I saw the finished product that I was aware the names had

been changed. My own afterthought contributions had missed the deadline anyway, but who

knows, perhaps Betty Boobsky might turn up in a future edition?

Like many who had played the original game I was

disappointed to see Anatol Fuckoff and Andrei Pissin purged, but this was expected so no

resistance was offered. Don also asked me to come up with some alternative names for the

characters as it was felt that the Teutonic humour of the originals would be lost on the

English speaking market. I demurred; apart from having a sentimental attachment to Tigran

Zenjarplan et al, I felt that they added atmosphere to what was already a

'foreign' game. Attempting to change the names into jokey English ones seemed

unnecessary, though I did agree to come up with two to replace Anatol and Andrei. As I

didn't hear from Don again on this point I assumed that the originals were to be

retained. It wasn't until I saw the finished product that I was aware the names had

been changed. My own afterthought contributions had missed the deadline anyway, but who

knows, perhaps Betty Boobsky might turn up in a future edition?